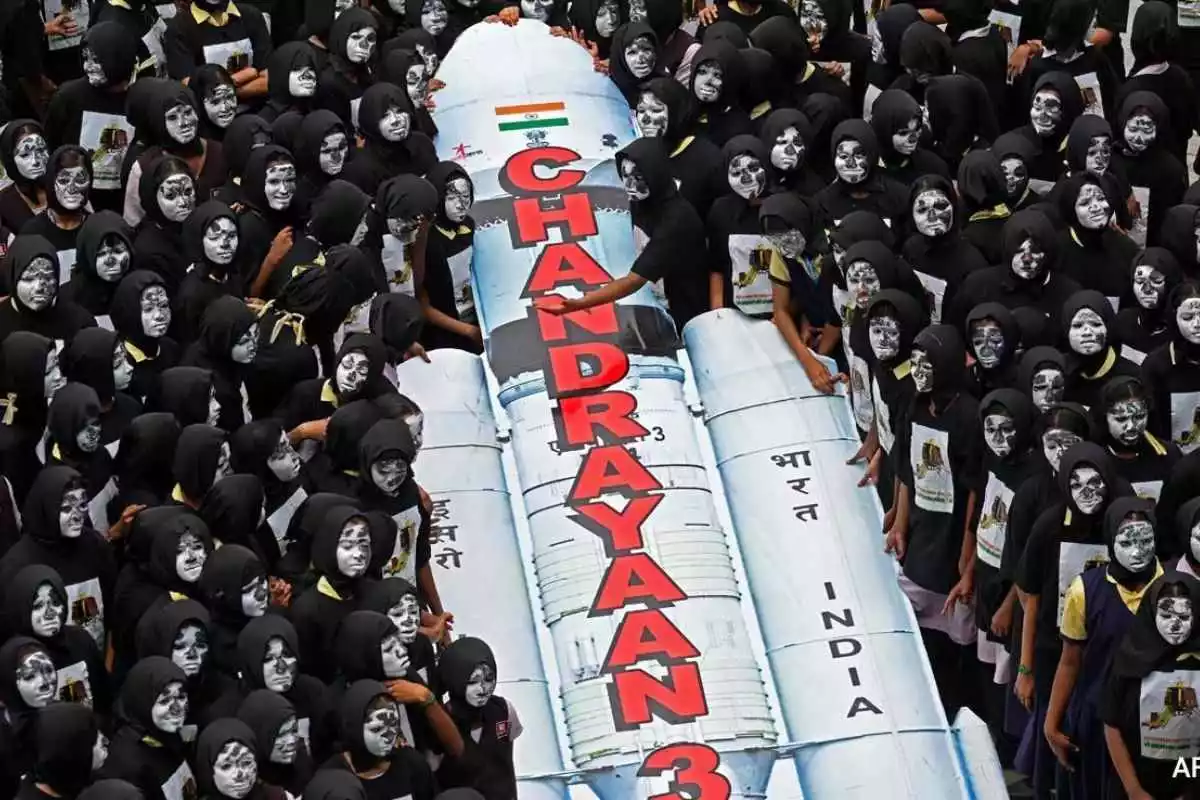

Representative image

Bengaluru/Washington: This week, India hopes to win the space race by becoming the first country to set foot on the moon’s south pole. The competition is about science, politics of national pride, and a brand-new frontier: money.

Wednesday will see the landing of India’s Chandrayaan-3 on the lunar south pole. Analysts and businesspeople predict that if it is successful, the South Asian country’s fledgling space sector will get an immediate boost.

Before the lander dropped from orbit, observers say, taking with it potential financing for a follow-up mission, Russia’s Luna-25, which launched less than two weeks ago, was on pace to arrive first.

The suddenly unexpected race to reach a previously uncharted area of the moon brings to mind the space race between the United States and the Soviet Union in the 1960s.

But now space is a business, and the moon’s south pole is a prize because of the water ice there that planners expect could support a future lunar colony, mining operations and eventual missions to Mars.

With a push by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, India has privatised space launches and is looking to open the sector to foreign investment as it targets a five-fold increase in its share of the global launch market within the next decade.

If Chandrayaan-3 succeeds, analysts expect India’s space sector to capitalise on a reputation for cost-competitive engineering. The Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) had a budget of around just $74 million for the mission.

NASA, by comparison, is on track to spend roughly $93 billion on its Artemis moon programme through 2025, the U.S. space agency’s inspector general has estimated.

“The moment this mission is successful, it raises the profile of everyone associated with it,” said Ajey Lele, a consultant at New Delhi’s Manohar Parrikar Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses.

“When the world looks at a mission like this, they aren’t looking at ISRO in isolation.”

RUSSIA’S CRUNCH

Despite Western sanctions over its war in Ukraine and increasing isolation, Russia managed to launch a moonshot. But some experts doubt its ability to fund a successor to Luna-25. Russia has not disclosed what it spent on the mission.

“Expenses for space exploration are systematically reduced from year to year,” said Vadim Lukashevich, an independent space expert and author based in Moscow.

Russia’s budget prioritisation of the war in Ukraine makes a repeat of Luna-25 “extremely unlikely”, he added.

Russia had been considering a role in NASA’s Artemis programme until 2021, when it said it would partner instead on China’s moon programme. Few details of that effort have been disclosed.

China made the first ever soft landing on the far side of the moon in 2019 and has more missions planned. Space research firm Euroconsult estimates China spent $12 billion on its space programme in 2022. But by opening to private money, NASA has provided the playbook India is following, officials there have said.

Elon Musk’s SpaceX, for example, is developing the Starship rocket for its satellite launch business as well as to ferry NASA astronauts to the moon’s surface under a $3-billion contract.

Beyond that contract, SpaceX will spend roughly $2 billion on Starship this year, Musk has said.

U.S. space firms Astrobotic and Intuitive Machines are building lunar landers that are expected to launch to the moon’s south pole by year’s end, or in 2024.

Additionally, privately funded alternatives to the International Space Station are being created by businesses like Axiom Space and Jeff Bezos’ Blue Origin. Axiom reported raising $350 million from Saudi and South Korean investors on Monday.

Space is still dangerous. India’s most recent moon mission failed in 2019, the same year an Israeli startup’s bid to make history by becoming the first privately funded moon mission also failed. This year, the Japanese startup ispace attempted an unsuccessful landing.

“Landing on the moon is hard, as we’re seeing,” said Bethany Ehlmann, a professor at the California Institute of Technology and NASA collaborator on a 2024 mission to explore the lunar south pole and its water ice.