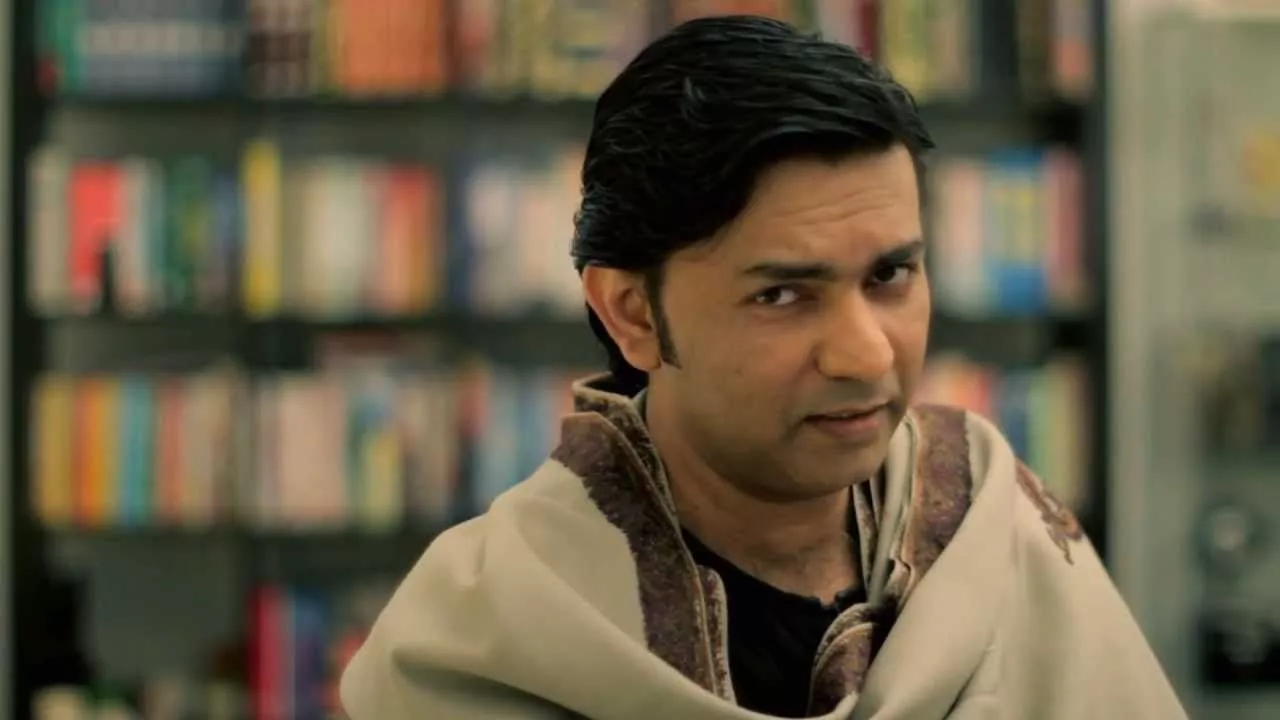

Pakistani Musician, Sajjad Ali

“Je aithon kadi Ravi langh jave,

Hayati Punjabi ban jave,

Main bediyan hazaar tod lan,

Main pani cho saah nichod lan.”

If the wonderful river Ravi passes through here, Punjab will be here, I’ll know it. I would disregard all limitations and draw life from its holy waters. I have nothing but love for this song, which was originally performed by legendary Pakistani musician Sajjad Ali and is now popular on Instagram. It is true that this song captures the longing of those who are away from home; those who yearn for their childhood, familiar foods, friends, family, and the comforting warmth of their homeland. It undoubtedly captures the suffering experienced by a “Punjabi” who lives outside of Punjab. But if one digs deeper and listens to the song closely, something else can be heard as well.

“Je Ravi vich pani koi nai,

Te apni kahani koi nai,

Je sang beliya koi na,

Te kise nu sunani koi nai”

If Ravi ever runs out, I won’t have a legacy or a tale to tell.Who would care to hear my stories if my pals were no longer with me? The name Punjab, which means “Land of Five Rivers,” is a combination of the Persian words “Punj” (five) and “aab” (water). These rivers are the Beas, Ravi, Satluj, Chenab, and Jhelum. Chenab and Satluj flow in Pakistan, but Beas and Satluj primarily flow through Indian Punjab. The only person who flows in both nations is Ravi. Therefore, while discussing our shared traditions and heritage, references to it are frequently heard on both sides of the border.

On either side of the border, graveyards of heartbreaking music and poetry about lost love and broken dreams, rivers and stories told on their banks, kids and kites they flew in shared skies, a bride’s wail upon leaving home, and friends who reflect on the past on chilly winter evenings are frequent places where the ghosts of India’s partition can be seen roaming. These lyrics break through geographical barriers, erasing distinctions that are tense with racial tension and political unrest.

The shared river, known as “Ravi,” flows through nations that share a mother, but they are now split apart by the loss of their traditions, languages, foods, and festivals; despite sharing common ancestry, there is nothing that can bring them together. ‘Ravi’ serves as a reminder of our shared history and culture. On the surface, it may appear that the poem is an homage to “Pardesis” (those who leave their own countries and move abroad), but on a deeper level, it is more like a lament, a scream for the loss of familiarity of homes, people, dreams, and hopes, as well as of lost legacies and friends left behind. The half they were able to gather and take with them, as well as the halves that were lost to them. The lives and emotions that were left behind and the materialistic belongings they brought along with them.

The rivers of Punjab aren’t just rivers, they have a metaphorical significance: borders might have been drawn, movement restricted, pain and pathos and turbulence created for man, by man but the free flow of nature has superseded geographical boundaries and rivers flow on their path, just the same, for you in Lahore and me in Amritsar. A melody like ‘Ravi’ is a sparkling example of this. As is evident from the warm response it got in India.

Nonetheless, ‘Ravi’ is not an isolated example. In 2015, Gurdas Mann and Diljit Dosanjh added a whimsical reference to the song ‘Ki Banu Duniya Da’ which was originally sung by Pakistani singer, Sarwar Gulshan, years ago.

“Sanu sauda nahi pugda

Ravi to Chenab puchda

ki haal e Satluj da…”

We had to pay a very high price for partition. River Chenab asks her sister River Ravi about the well-being of their brother Satluj.

“Painde dur Peshawar’an de oye

O Wagah de border te

Raah puchhdi Lahore’an de haye…”

The road to Peshawar is far and distant to reach. At the Wagah border, I look for paths that once led to Lahore but sadly don’t exist anymore.

Again, what comes across is the intense longing and pain of being separated from loved ones who were once very dear but now are lost forever. The song says Chenab asks Ravi about Satluj… isn’t this symbolic? Doesn’t it render a feeling of nostalgia? Imagine the plight of people who traveled across borders and made lives for themselves in a foreign land but could not forget their roots, yet did not have any hope of visiting their loved ones or ancestral homes again, ever. Think of the twin cities of Amritsar and Lahore, having the same culture, shared languages, and similar food habits. Isn’t it torturous that although they still share the same seasons, speak a similar language, and experience the same emotions, these people are ‘supposed’ to feel animosity rather than camaraderie? Shouldn’t love and nostalgia be the most natural emotions they should be feeling for having lost what they valued the most?

There’s another rendition by Piyush Mishra called ‘Husna’ which is about a lover remembering the old times spent with his beloved. Now they are separated by borders, but everything, even the shedding of autumn leaves, reminds him of her. He goes on to ask her whether trees shed leaves in the same way in Pakistan also. Does the sun rise there in the way it does here? He Still thinks about the folklores of ‘Heel-Ranjha’, Bule Shah’s poetry, the festival of Eid, celebrations of Diwali, and the taste and texture of ‘seviyan’.

“O Husna meri ye toh bata do

Lohri ka dhuan kya ab bhi nikalta hai

jaise nikalta tha

us daur mein vahan…”

He talks about the pre-partition times and cannot come to face the reality that they are in different countries which were once undivided. The man, Javed, wants to understand what has changed and how?

“Ye Heeron ke Ranjhon ke nagme

Kya ab bhi sune jaate hain vahan?

aur rota hai raaton mein

Pakistan kya vaise hi

jaise Hindustan ?”

I don’t see the need to translate these lines. They are so tragic and melancholy, yet so true! They bring out the pining for the times when there were no borders, no animosity between religions, and no hatred. When love and brotherhood were essential communal codes. When Holi and Eid were celebrated with equal fervor. When Akash and Ali were brothers.

Over seven decades have elapsed since India and Pakistan were carved into separate entities. Punjabis were compelled to leave everything behind and uproot their lives, a distressing consequence of the decisions taken by a cadre of divisive politicians, advocating for a separate Muslim state. Years later, people eventually moved on with their lives, yet they never lost the looming sense of helplessness and grief at having left parts of themselves behind. Some of them penned down their nostalgia in the form of stories and poems and those who could not do so take refuge in such melodies, as writers and poets are their spokespersons who put popular feelings and emotions into words.

But it makes me wonder how things would have been different if there had been no boundaries. People would undoubtedly be happier and more grounded, but what about these eerily lovely songs and verses? If the sorrow of separation didn’t exist, would they still be as sincere? If the Chenab and Jhelum had continued to flow through Indian Punjab, would nostalgia still cling to our hearts and cause us to cry? Would Javed be content if ‘Husna’ had remained in Lahore? If there had been no-man’s-land and barbed wire fences between Amritsar and Lahore today, would there have been motorways with moving traffic? I’m unsure.

(This story has not been edited by Bharat Express staff and is auto-generated from a syndicated feed.)